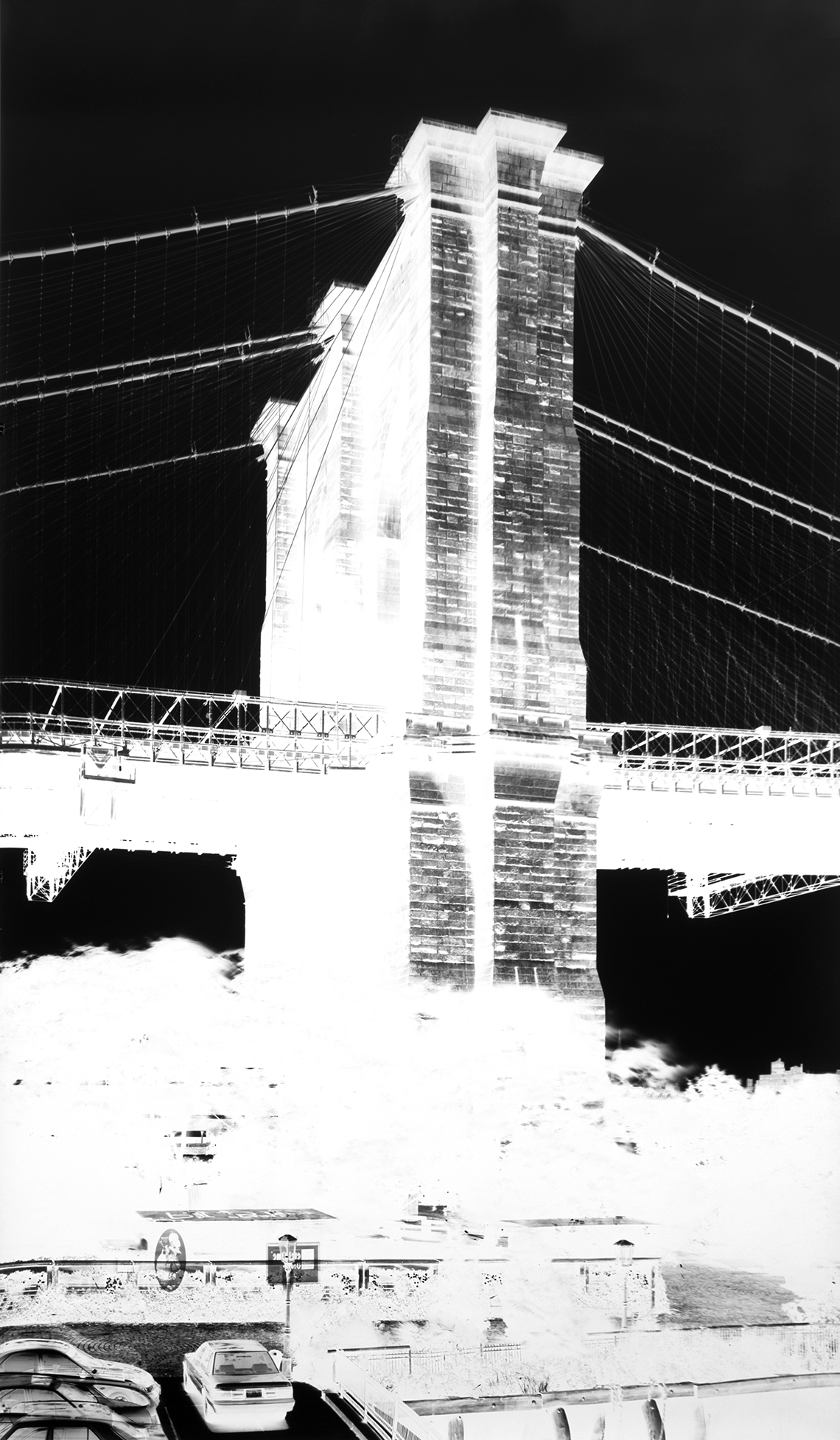

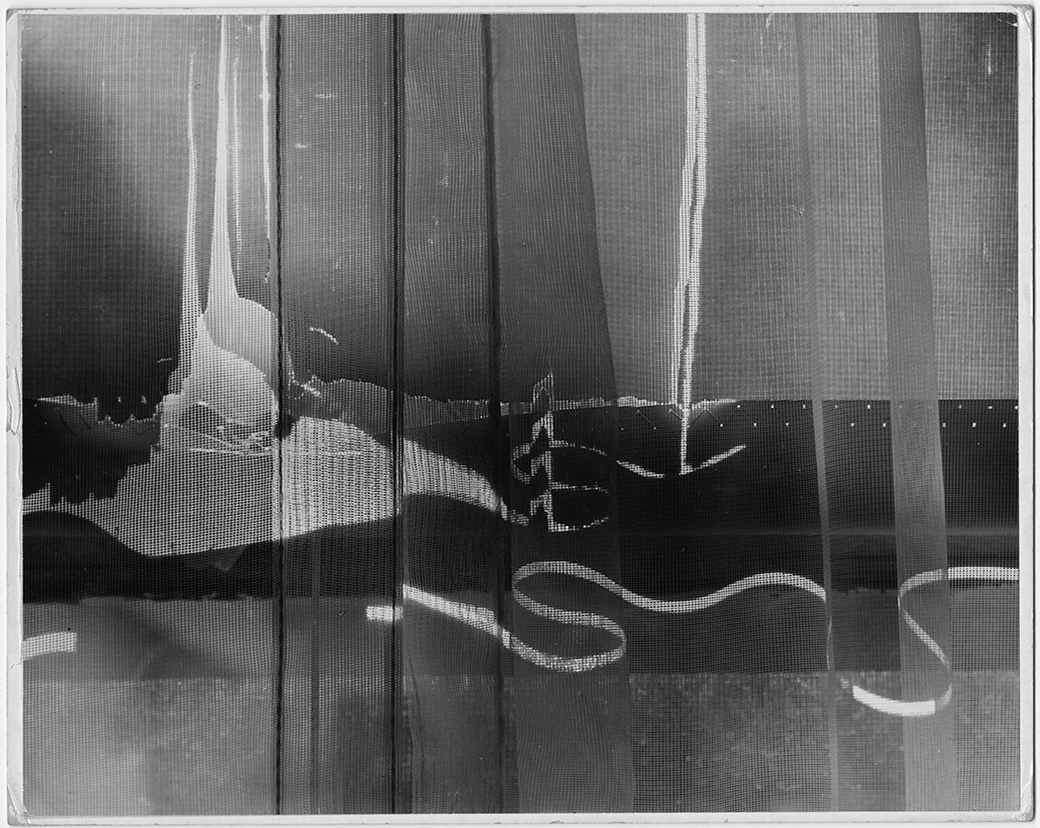

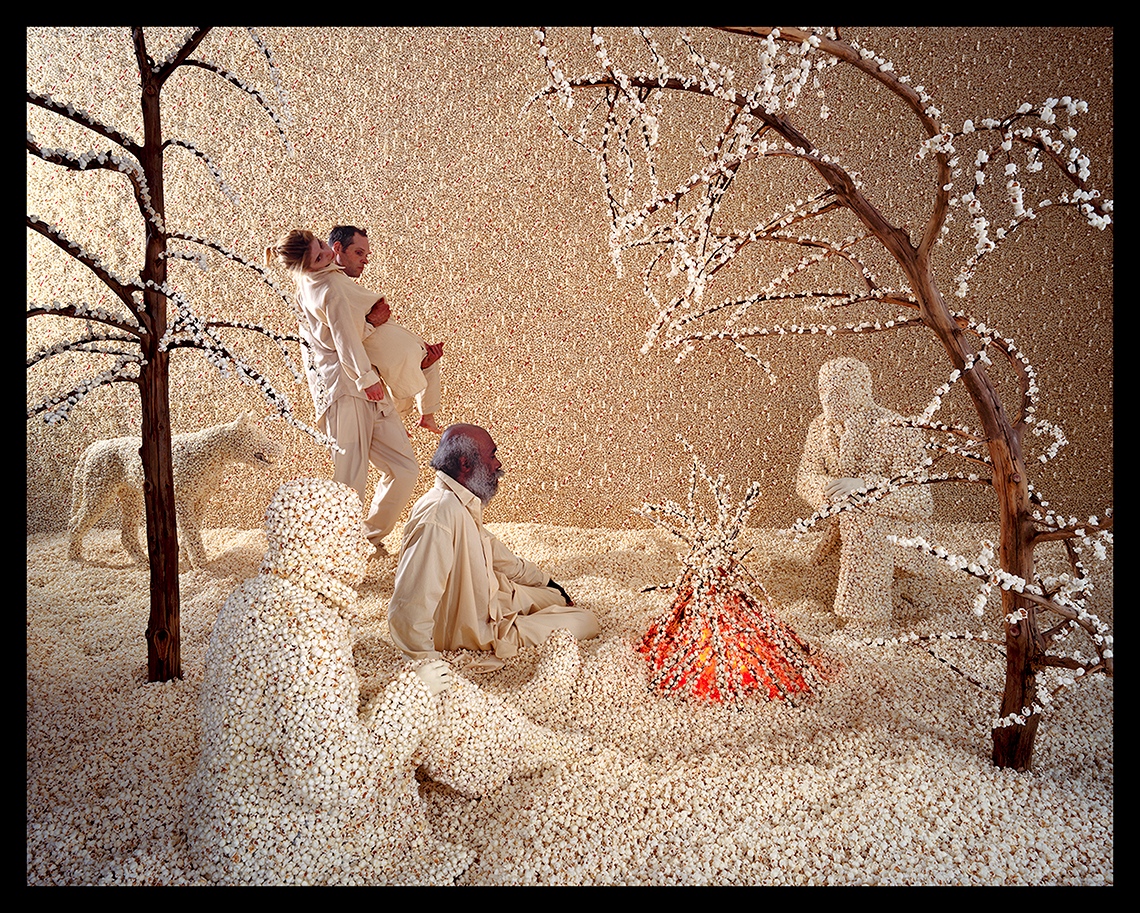

Picasso once said, “art is a lie with which I tell the truth.” In this section, artists use photographic media to construct images that may appear at first to be mere recordings of the world. Techniques that fabricate reality include staging fictions, painting on the photograph, printing from multiple negatives or digitally combining many negatives. Long exposures allow movement to transform figures, and artists can alter the pace of perception. Other photographers may simply notice how time bends, sometimes helping that perception through darkening and/or lightening selectively, or how the world is constructed by others. Whatever approach or technique is used, the outer world is metamorphosed through the artist’s vision.

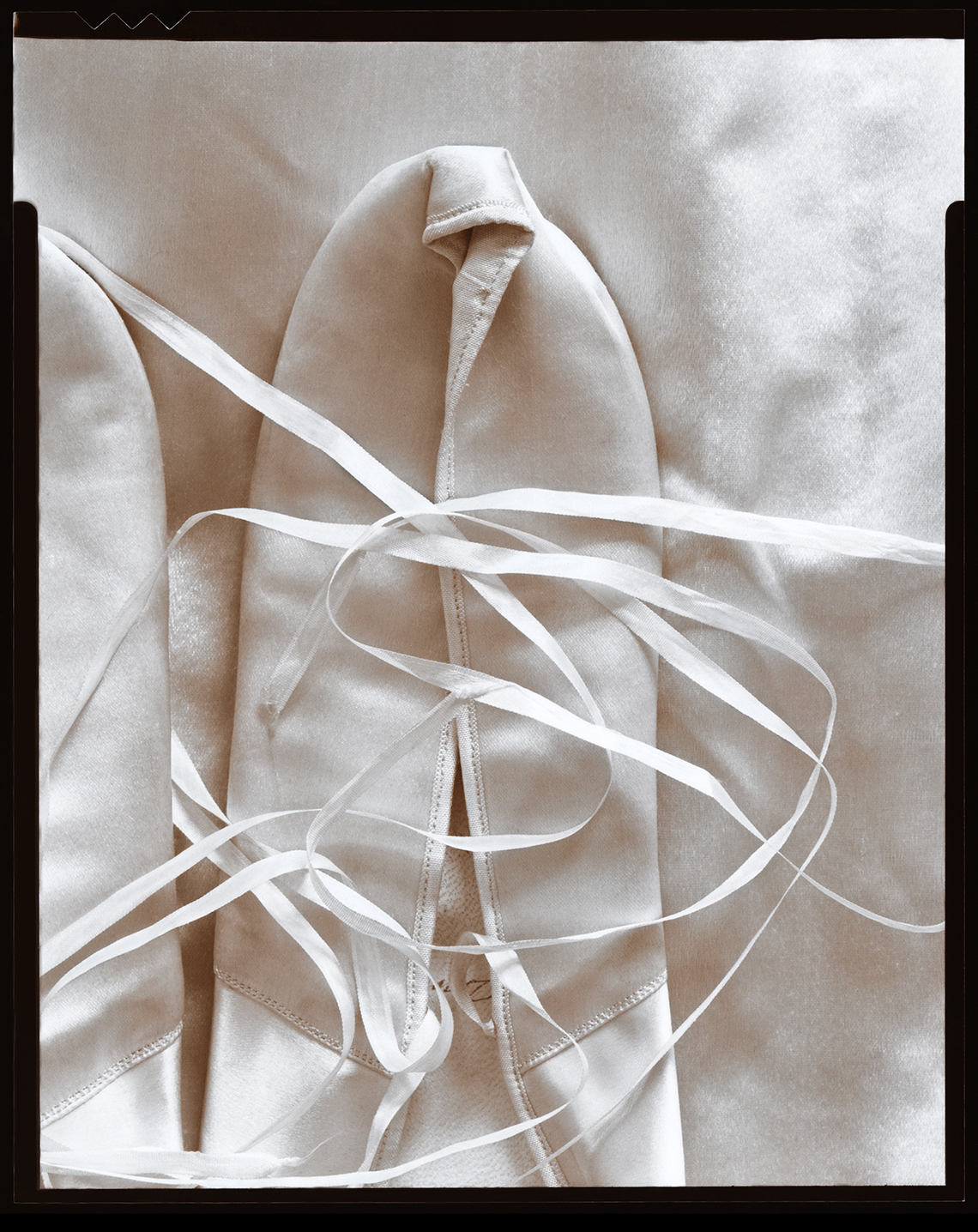

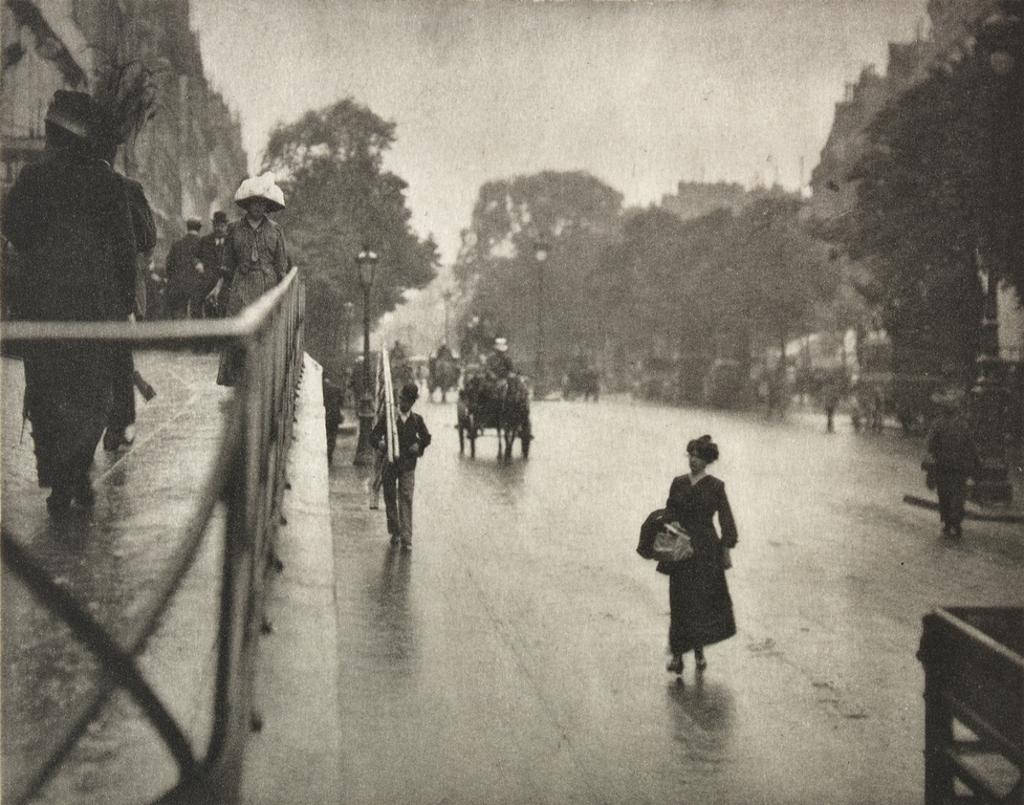

This section reveals how many artists use photographic media to emulate other media or to achieve the same aims, a freedom taken for granted in painting, printmaking, film and architecture. No one criticizes the imitation in wood of stone columns, but photography has throughout its history been reviled for its frequent desire to evoke or emulate painting and printmaking. In fact, photography shares with all other media the aesthetic aims of its historical period, including in our own time. Here we show evocations of various artistic traditions that necessarily emulate other media, sometimes ironically and sometimes movingly or amusingly, but always consciously. In some cases, the photographer works within a well-established tradition, with a twist; in others, the photographer was a part of a larger modernist movement, as with Alfred Stieglitz’s participation in the Symbolist movement. In others, the artist purposely uses photography to comment on the traditions we have all inherited and their relation to photographic processes. And, to turn the tables, photography underlies many works that we do not view as photography at all. As Alvin Langdon Coburn said in 1916, “if it is not possible to be ‘modern’ with the newest of all the arts, we had better bury our black boxes” (referring to the 4” x 5” Graflex camera used by many artists of his day).

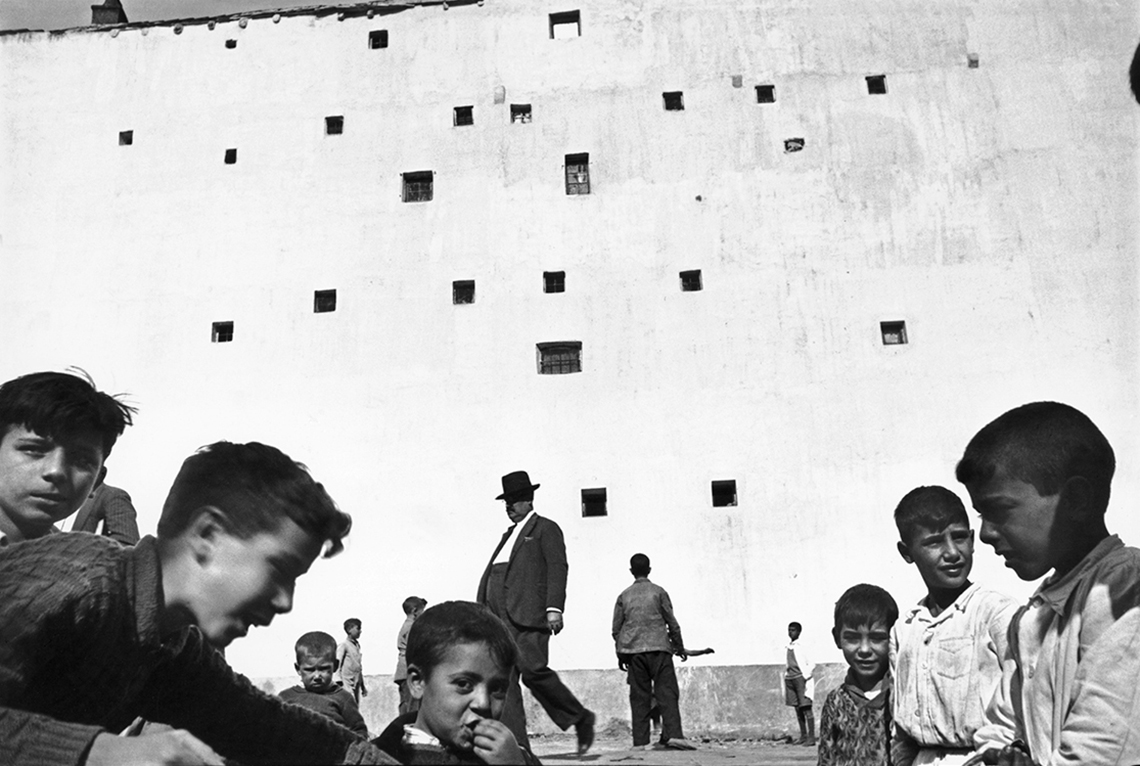

Many of the techniques that the previous sections have highlighted are also operative within the seemingly sacrosanct realm of photographic portraiture. From daguerreotypes to mug shots and from documentary to frank fictions and manipulations, photographers interpret and construct identities as well as pointedly observe how society shapes the individual. Children especially seem vulnerable to social forces, but all presentations of human beings as individuals must grapple with the person’s identity and self-presentation. Some of these works reveal the subject’s awareness of the photographer, some muffle it. With portraiture, the conditions of the social situation—in which the photographer is also implicated—have everything to do with the resulting revelation of identity.