Paradise with a Purpose

Doris Duke (1912 –1993), known for her wealth and philanthropy, surprisingly amassed one of the nation’s largest private collections of Islamic art. Perhaps equally surprising is the environment Doris created to house her remarkable collections: Shangri La, a five-acre estate overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Honolulu, Hawai‘i. Begun in the mid-1930s and developed over the course of more than 50 years, Shangri La seamlessly melds modern architecture, tropical landscape and art from throughout the Islamic world. Representing an approach that may be termed “inventive synthesis,” Shangri La mixes original and commissioned architectural elements. Shangri La’s collections are equally diverse and encompass a broad time spectrum, from the pre-Islamic and Medieval periods through the mid-20th century, as well as myriad media, styles and techniques developed within the realm of Islamic art.

Doris Duke’s Shangri La: Architecture, Landscape, and Islamic Art at the Nasher Museum marks the first time works from Doris Duke’s Islamic art collection have traveled to North Carolina.

Shangri La, which began as a secluded place of rest, was energized by Doris’ restless imagination, aesthetic drive and seriousness of purpose. In her will, Doris opened the house’s doors by establishing the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, which owns and manages the site and collections for the purpose of promoting the study and understanding of Islamic arts and cultures. Doris Duke’s Shangri La is the first exhibition to allow audiences, beyond visitors to the house, the opportunity to experience Shangri La’s distinctive blend of architecture, landscape and Islamic art. To achieve this purpose, 60 works of Islamic art are featured alongside architectural sketches, archival photographs and videos and large-scale color photographs of the estate. In addition, eight artists who have participated in Shangri La’s artist-in-residence program have contributed new work to the exhibition. Created in a variety of media, this art captures their different responses to Shangri La’s site, its collections and Doris Duke’s enduring legacy as a collector.

Captions for slideshow above in order of appearance: 1) Mosaic tile panel in the form of a gateway, Iran, probably nineteenth century. Stonepaste: monochrome-glazed, assembled as mosaic. On the dining room lanai. © 2011 Tim Street-Porter. Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. 2) The Playhouse at Shangri La. © 2011 Tim Street-Porter. Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. 3) Doris Duke and James Cromwell pose by the Jali Pavillion at Shangri La, 1939. Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Historical Archives, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University. Photo by Martin Munkacsi. 4) Iranian (Isfahan), Lunette (detail), 1938-39. Stonepaste: monochrome-glazed, assembled as a mosaic; 11 ¼ x 22 ¾ x 3 ½ inches (28.6 x 57.8 x 8.9 cm). © 2011, Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. Photo by David Franzen. 5) Mosaic tile panel in the form of a gateway, Iran, probably nineteenth century. Stonepaste: monochrome-glazed, assembled as mosaic. On the dining room lanai. © 2011 Tim Street-Porter. Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i.

Quote: Doris Duke’s Shangri La: A House in Paradise / Architecture, Landscape, and Islamic Art, p. 5

Doris Duke

Doris Duke was born in 1912, the only child of James Buchanan Duke and Nanaline Holt Inman. “Buck” (as Doris’ father was called), along with his brother Benjamin and father, Washington Duke (for whom the university is named), founded the American Tobacco Company; on his own, Buck also founded the Duke Energy Company. He died in 1925 when Doris was 12 years old, leaving his young daughter about $80 million to be parceled out during her lifetime, beginning on her 21st birthday.

In 1935, at the age of 22, Doris married James Cromwell, an aspiring politician and member of the Stotesbury family of Philadelphia. The two newlyweds went on a 10-month-long honeymoon, visiting Egypt, India, Indonesia, China and Japan. After seeing the Taj Mahal, Doris commissioned architect Francis Blomfield of Delhi, India to design a marble bedrom and bathroom suite for a home she planned to build in the U.S. Traditional craftsmen with the Indian Marble Works in Agra executed the carved marble and inlay work: designs which became the nucleus of Shangri La’s Mughal Suite and mark the beginning of Doris’s Islamic art collecting.

After Doris and James divorced in 1943, Doris maintained ownership of her properties, which included, in addition to Shangri La, an estate in Newport, Rhode Island; the 2,000-acre Duke Farms in Somerville, New Jersey; and the mansion at East 78th Street in Manhattan, which Doris eventually gave to the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Although Doris would have a hand in renovating and restoring these properties, Shangri La remained the only home she ever built herself, and she was intimately involved in every decision of its design, as well as the selection and placement of the Islamic art it contained.

In addition to purchasing Islamic art, Doris used her monetary assets to assist in a wide range of causes, including medical research, architectural conservation and preservation, wildlife protection and child abuse prevention. Doris died on October 28, 1993, at the age of 80, with a net worth of nearly $1 billion. In accordance with her will, the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art was established in 1998 to promote the study and understanding of Islamic arts and cultures. The foundation is in charge of the management and preservation of Shangri La, which is used for educational programs and is open to the public. As part of its mission, Shangri La hosts contemporary artists and scholars researching Islamic art.

Captions for images on right (top to bottom): Image of Doris Duke at Shangri La by Horst / Vogue; © Condé Nast, 1966. Doris Duke at the Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque; 1647-53) in Agra, India, during her honeymoon with James Cromwell, 1935. Doris Duke Photograph Collection, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Historical Archives, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

SHANGRI LA

The final stop on Doris Duke and James Cromwell’s honeymoon was Hawai‘i. Originally planning to stay for two to three weeks, the couple fell in love with the seclusion and privacy the islands offered, extending their stay by three and a half months. Soon thereafter, the two decided to build a home in Honolulu rather than Palm Beach, Florida, where James’s mother lived. Fortunately, the Taj Mahal-inspired marble bedroom and bathroom suite plans that Doris had commissioned while in India were transferrable to this new estate. Doris named the new home “Shangri La” and described it as “a Spanish-Moorish-Persian-Indian complex.”

Designed by architect Marion Sims Wyeth and built between 1936 and 1938, Shangri La is believed to be named for the mythical hidden paradise in James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon. At the time, it was the most expensive home constructed in Hawai‘i, costing about $1.4 million to build.

The complex integrates a 14,000-square-foot house, a poolhouse known as the “Playhouse,” and a pool, comprising a series of interlocking spaces, both indoors and out: rooms, courtyards, lanais, terraces, lawns, gardens and numerous water features. Doris commissioned artisans in India, Morocco, Iran and Syria to create art and architectural elements for the main house and Playhouse, utilizing traditional forms, patterns, and means of fabrication. The house’s aesthetic is defined by an inventive synthesis, combining Islamic architectural details from buildings Doris saw on her travels with a simple, modernist design. The building provides a unique backdrop for Doris’s collection of Islamic art, and Doris continues to acquire and renovate for nearly 60 years after the estate’s initial construction.

In order to convey Doris’s Honolulu home, the exhibition includes architectural drawings, large-scale color photographs of the estate and an architectural model, as well as photographs and videos of Shangri La during its construction in the 1930s.

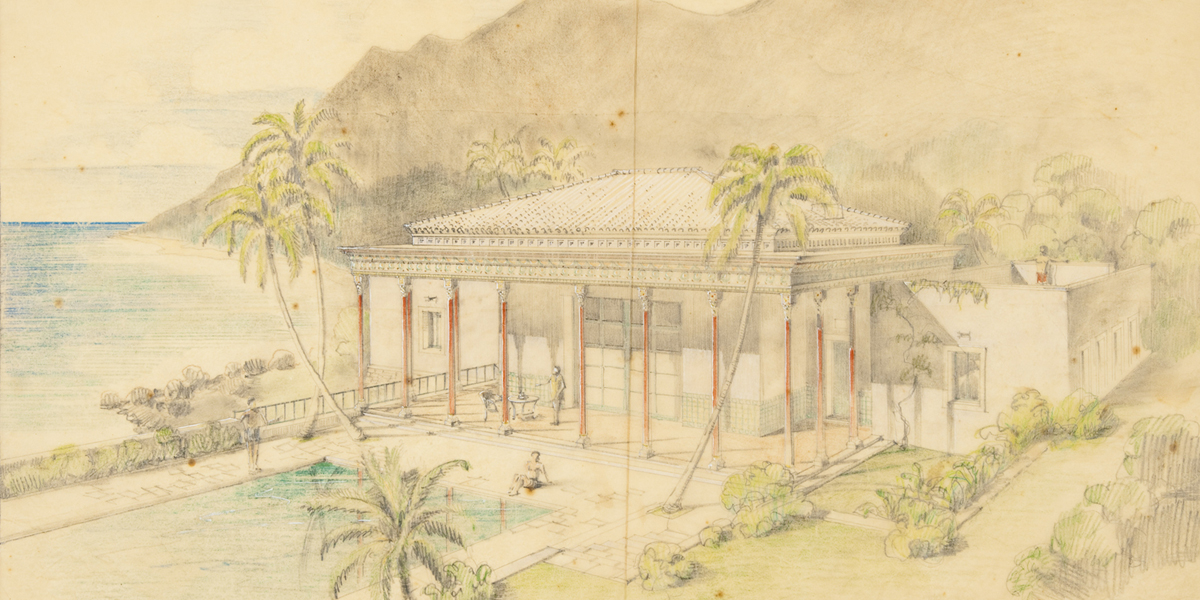

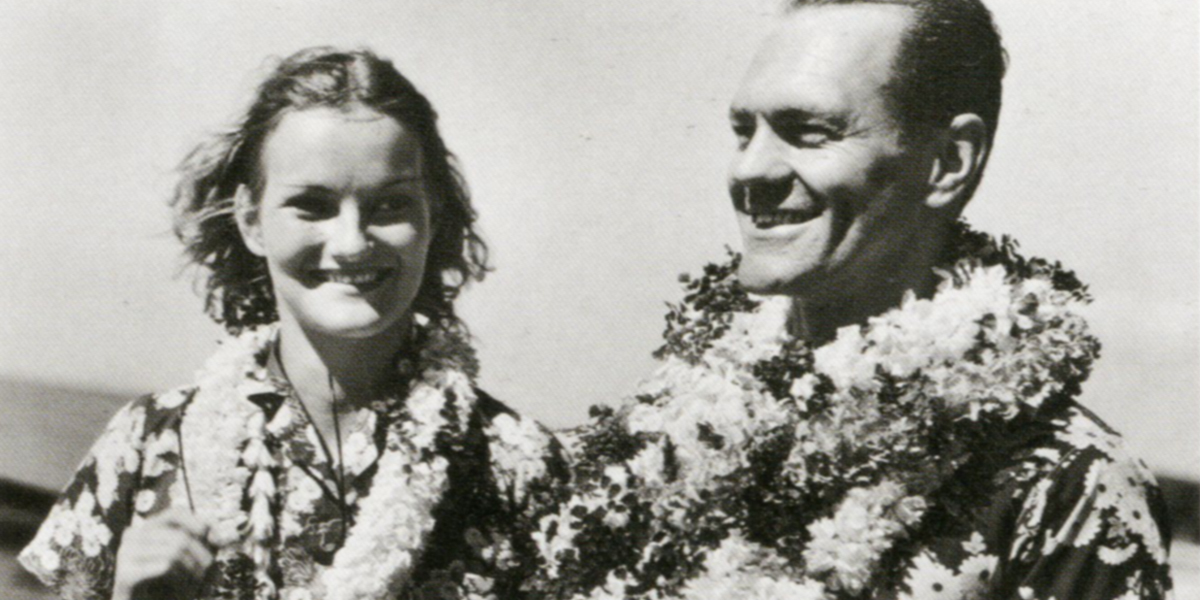

Images in Shangri La slideshow in order of appearance: 1) Conceptual drawing of Playhouse at Shangri La, ca. 1936. Colored pencil on tracing paper, 14 ¼ x 28 inches (36.2 x 71.12 cm). H. Drewry Baker, Wyeth & King, Architects. Shangri La Historical Archives, Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. 2) The Playhouse at Shangri La. © 2011 Tim Street-Porter. Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. 3) Two views of the bathroom in the Mughal Suite at Shangri La. © 2011 Tim Street-Porter. Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. 4) The Syrian Room at Shangri La. © 2011 Tim Street-Porter. Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. 5) Doris Duke and James Cromwell in Hawai’i, 1935.

Islamic Art

Doris Duke began to collect Islamic art in earnest while on her honeymoon in 1935. An intense three-year period of collecting followed and culminated in a trip to Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Egypt in 1938, the last major trip she took before the completion of Shangri La in 1939. In addition to her direct experience, Doris’s involvement with a loose network of individuals, including scholars, curators and dealers, informed her thinking and collecting.

Assembled over the course of almost 60 years, Doris’s collection of Islamic art consists of approximately 2,500 objects in a variety of styles and mediums from a range of countries and eras. The term “Islamic art” covers a wide range of places and dates and is not limited to one people or one style. Islamic art includes work created beginning in the 7th century in an area spanning North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, part of South and Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, as well as Spain and Turkey.

This range is the result of the historic expansion of Islam. As various Muslim groups controlled differing lands at different points in time, they shared their religion along with the techniques and styles characteristic of their art. While the terminology and categorization of Islamic art stems from a perceived relationship between the art and the dominant religion of the area and era it was created in, Islamic art encompasses both religious and secular works.

The 60 Islamic works in this exhibition come from Egypt, India, Iran, Morocco, Spain, Syria, Turkey and Uzbekistan—including works Doris commissioned for use at Shangri La—and were largely created between the 10th and 20th centuries. These objects take the form of a variety of mediums, such as textiles, ceramics, paintings, metalwork, glassware, jewelry, and furniture. They also represent the diverse styles, functions, and meanings encompassed by the designation of Islamic art.

Doris Duke began to collect Islamic art in earnest while on her honeymoon in 1935. An intense three-year-long period of collecting followed and culminated in a trip to Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Egypt in 1938, the last major trip she took before the completion of Shangri La in 1939. In addition to her direct experience, Doris’s involvement with a loose network of individuals, including scholars, curators, and dealers, informed her thinking and collecting. Assembled over the course of almost 60 years, Doris’s collection of Islamic art consists of approximately 2,500 objects in a variety of styles and mediums from a range of countries and eras. The term “Islamic art” covers a wide range of places and dates and is not limited to one people or one style. Islamic art includes work created beginning in the seventh century in an area spanning North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, part of South and Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, as well as Spain and Turkey. This range is the result of the historic expansion of Islam. As various Muslim groups controlled differing lands at different points in time, they shared their religion along with the techniques and styles characteristic of their art. While the terminology and categorization of Islamic art stems from a perceived relationship between the art and the dominant religion of the area and era it was created in, Islamic art encompasses both religious and secular works.

The 60 Islamic works in this exhibition come from Egypt, India, Iran, Morocco, Spain, Syria, Turkey, and Uzbekistan—including works Doris commissioned for use at Shangri La—and were largely created between the tenth and twentieth centuries. These objects take the form of a variety of mediums, such as textiles, ceramics, paintings, metalwork, glassware, jewelry and furniture. They also represent the diverse styles, functions and meanings encompassed by the designation of Islamic art.

Image above: Northern Indian, Hand mirror, 19th century. Jade, gold, gemstones and mica; 9.125 inches diameter (23.18 cm). © 2006 David Franzen. Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai‘i.

Contemporary Art

Images above, top to bottom: Shahzia Sikander, Unseen 1, 2011. HD-digital projection, dimensions variable. Photo by David Adams. Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Honolulu, Hawai’i. Mohamed Zakariya, “And His throne was on the water” (Qur’an 11.7), 2011. Gold leaf over acrylic on synthetic canvas, 53 ¼ x 41 ¼ inches (135.26 x 104.78 cm). Photo by David Franzen.